When some of Tiny Mile’s initial prototypes had begun to make their rounds on the city streets, the service industry was in the midst of its own tumultuous evolution. Outdoor patios would once again remain spotless and unused for the summer season; customers were sequestered to the safety of their homes, while businesses struggled to reach their doorsteps; “CLOSED” signs adorned their doors and, unfortunately for some, were never removed. COVID-19 had just entered its second year.

The global pandemic, with its precautions of self-isolation and minimal interaction, was a chance to develop both our robots and values in parallel with an isolating, unpredictable period, where contactless methods of delivery had become a key source of stability, online revenue was now a deterrent against declining profits, and web-based services were redefining themselves as a potential lifeline. It presented to us an alien landscape, now accompanied by the equally alien presence of delivery robots, and remains a deeply informative time for us because it gave the team a glimpse of the vital, yet tenuous relationship between consumers, businesses, and new technologies.

Now, online delivery platforms have become ubiquitous, coronavirus notwithstanding, strengthening this relationship further by moving beyond putting ready-made meals on the table, and into retail, groceries, and pharmaceuticals. And with this growth, as e-commerce plays an essential role in helping shift the marketplace from corner stores to smartphones, the equability of this service continues to be a critical issue for communities with limited access to their benefits.

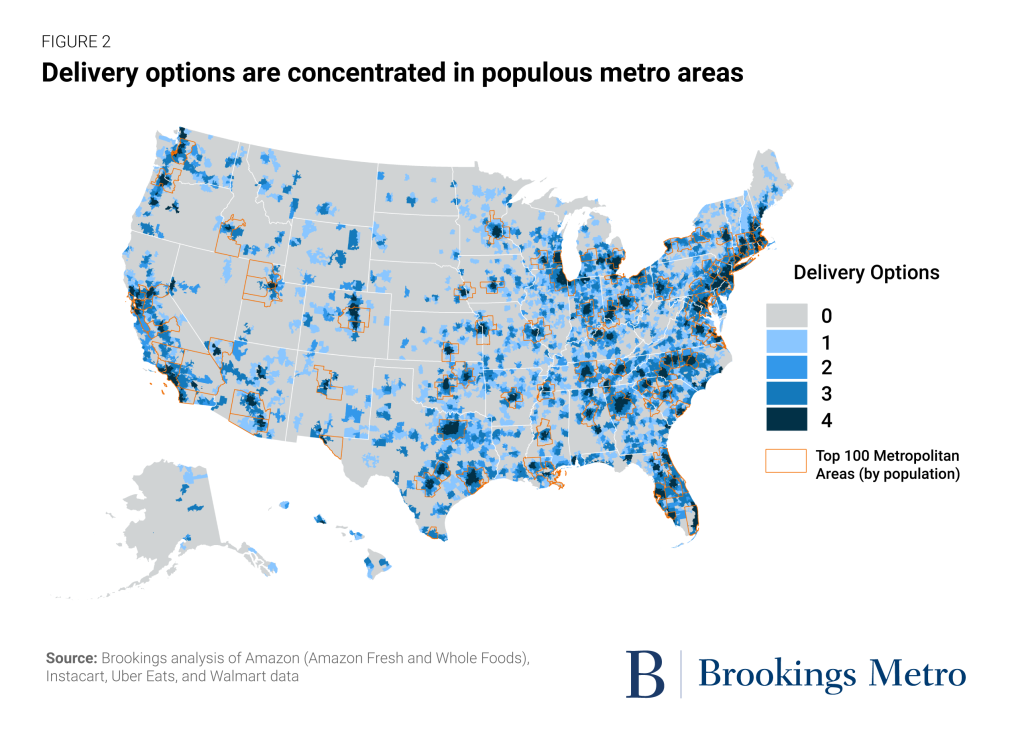

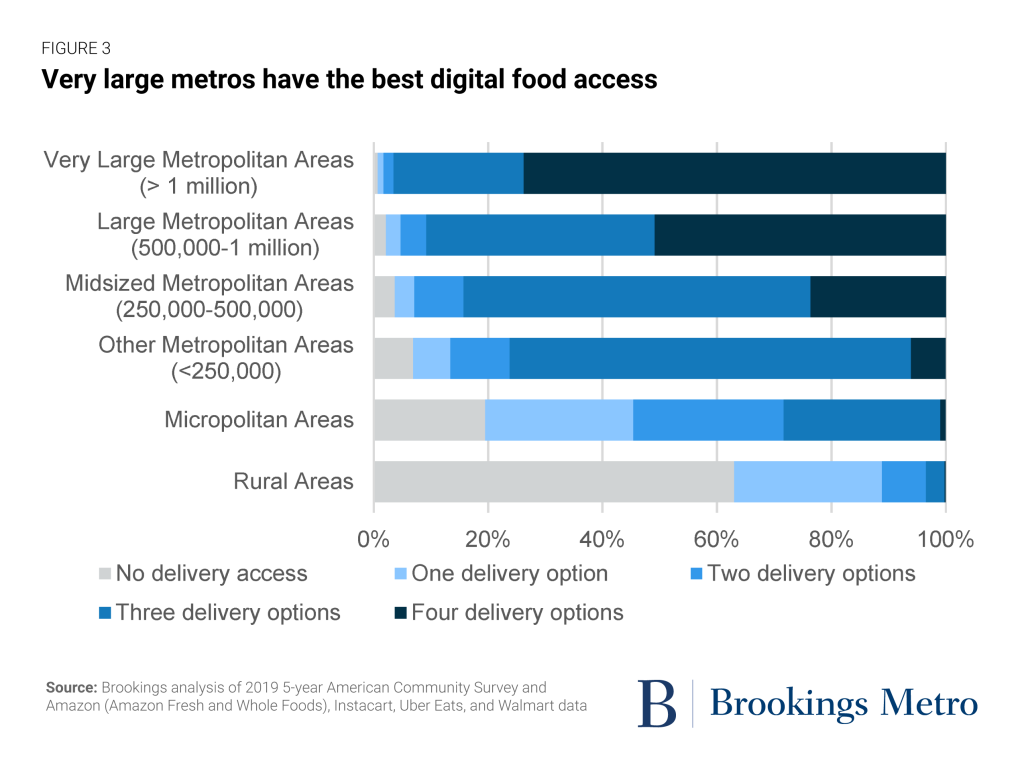

A recent study from the Brookings Institution used delivery zone data from Amazon (Amazon Fresh and Whole Foods), Instacart, Uber Eats, and Walmart in order to geographically evaluate digital food access in the United States. Researchers found the rate of availability to be largely positive, with at least one of these four platforms reaching 90% of residents living in “low-income, low-access tracts,” traditionally defined as “food deserts.”

The shortage affecting these neighborhoods appears at first to simply be a matter of geography; with the limited ability to purchase fresh, affordable meal options within distance from residents’ homes, fast food chains, convenience stores, and cheap, processed foods are available in excess to residents with few alternatives. However, while the exponential growth of online delivery services could potentially help bridge the gap and reach these disinvested parts of the U.S., confusing options with access oversimplifies the issue.

“Just as living within a certain geographic proximity to a grocery store does not mean someone has perfect access to food in the brick-and-mortar food system, not everyone living in a delivery zone has perfect digital access to food.” — Caroline George and Adie Tomer, The Brookings Institution

Brookings’s analysis found that although many of the major delivery services do indeed reach residents in areas classified as food deserts, this availability alone does not remedy their insecurity. Underlying, neighborhood-level disparities, such as access to broadband connection, affordability of either the service or its products, and population density are among some of the socio-economic factors that restrict these platforms’ use. In fact, demographics appeared to be a key correlating factor for delivery access, with many platforms concentrating their services in areas with significantly higher population densities than that of smaller, less advantageous communities.

Source: Brookings Institution

On the surface, this may seem contradictory to a digital age, where its expansion is predicated on eliminating barriers, not creating them. Much in the same way that the advent of the internet made information easily attainable and its distribution instantaneous, so too are we still exploring the limitations of an online marketplace. As increasingly more services migrate online, new potential revenue pools, including dark kitchens, virtual branding, and miniaturized “pickup lockers,” supplant brick and mortar businesses to the extent that notions of location and how that may affect equitability appear increasingly antiquated.

And yet, data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reveals that the issue is a multi-faceted one. Several key indicators are used in socio-economic assessments to accurately measure food accessibility in a given neighborhood, including accessibility to sources of healthy food (e.g. the availability of stores and grocers), individual-level resources that may affect accessibility (e.g. income), and neighborhood-level indicators of resources (e.g. public transit).

The problem with deserts, it seems, is that they’re no longer geographical in nature. It’s based on where you can purchase healthy options, the resources limiting your ability to purchase them, and the neighborhoods that help define the resources at your disposal. In a marketplace absent of geography entirely, spanning across networks, distance can instead manifest in individuals rather than places, when people are low on time, low on cash, low on transportation, low on digital literacy or computer access—in ways that are not always easy to identify or address.

Nor is the problem one that digitization alone can remedy. In some cases, online delivery can potentially aggravate it; with the relatively new prominence of e-commerce, a lack of sufficient support has now extended from consumers to the marketplace itself. For many small businesses, who lack the resources or reach of their franchisee counterparts, digitized delivery is a financially and technologically infeasible option. Consequently, without an adequate infrastructure in place, business owners, their customers, and traditionally disinvested communities remain unrecognized online, allowing for the monopolization of digital distribution by much larger competitors.

The desert metaphor is apt; it suggests scarcity, and describes a simultaneous abundance of poor choices. But rather than online marketplaces reinvigorating previously dry, untended landscapes, they’ve instead established a series of small, digital oases - fortifying, opulent, and, unfortunately, rarely encountered.

Digital distribution promises convenience, affordable prices, and fast, reliable service. And just as the service industry has evolved in response to the growth of e-commerce, so too should our previous understanding of food accessibility be reflective of the many complex, underlying factors impacting disinvested parts of the city.

To help meet this demand for neighborhood-focused delivery, earlier this year we partnered with city officials in Charlotte, N.C.,Odeko, and Undercurrent Coffee to launch a program dedicated to promoting low cost delivery to locally-owned businesses. Working directly with both the City and small business owners, our goal was to gain insight on how modernized methods of delivery, such as remotely-controlled robot couriers, could help develop an infrastructure that’s sustainable, supports small communities, and improves local businesses’ ability to compete in the market.

Neighborhood-level programs such as this have become crucial in a digital age where app and web-based delivery is so widespread, and the success of our initial pilot has allowed us to begin investigating the further expansion of Tiny Mile to new, previously unexplored areas where we can not only make a positive impact, but reinvent the ways in which these socio-economic disparities have been traditionally addressed with strategies that are at once modern and inclusive.

In using delivery robots to develop a service that’s affordable and community-focused, we can help bridge the gap and empower local businesses, as well as promote a much healthier, diverse business ecosystem where fast food fare and convenience store cuisine are no longer the only options for dinner tonight.

Are you interested in partnering with Tiny Mile? Is there a local brand you’d love to see us support? Contact our team today.